As I’ve acknowledged in various other posts from my spring 2016 study tour to Japan I am forever grateful to Aiah Noack of Naturplanteskolen in Denmark for organising the tour of sansai farms near to the city of Toyota and for the on-the-ground assistance and translation by her plant breeding friend, Teruo Takatomi, and colleagues who had kindly offered to organise a tour of farms for a couple of days. If you’re not familiar with the term sansai, it literally means mountain vegetables, previously wild foraged vegetables nowadays farmed for markets near the urban areas.

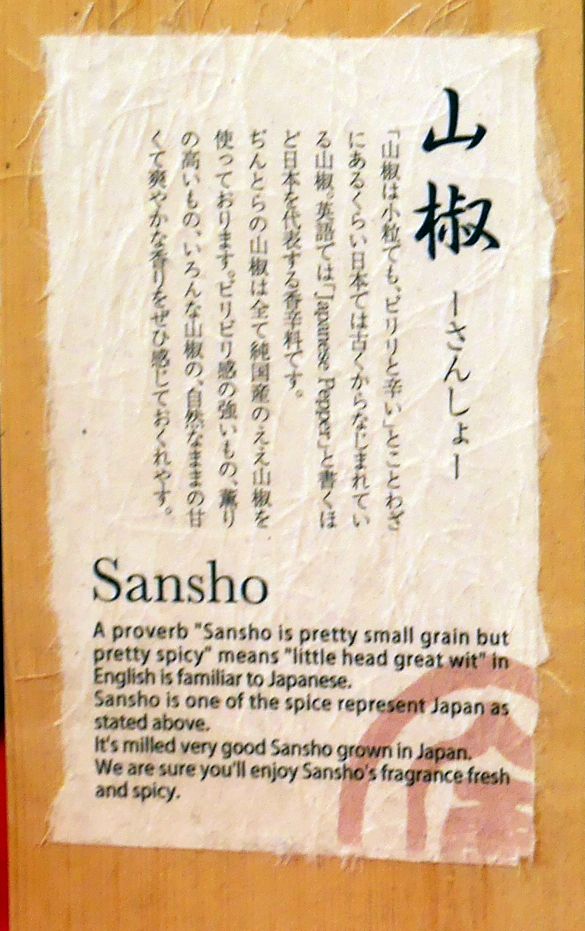

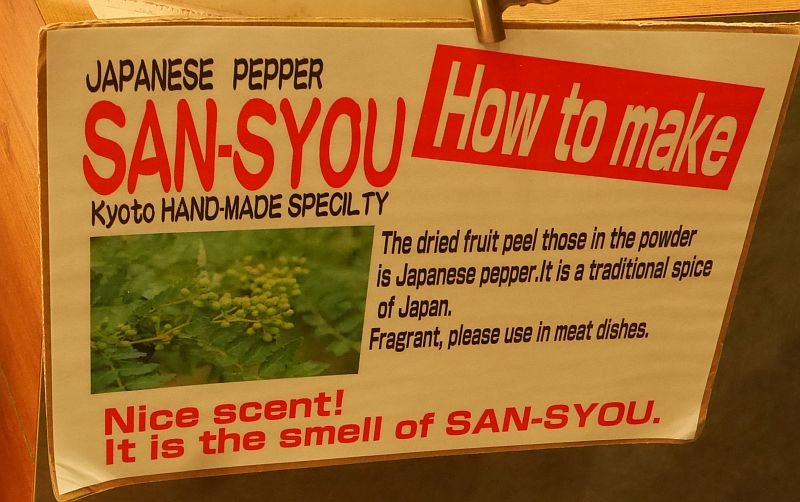

Before meeting Teruo we spent a couple of days in Kyoto and visited the Nishiki market to familiarise ourselves with local vegetables. Here, the importance of sansho (san as in sansai meaning mountain and sho, pepper) or Japanese pepper (Zanthoxylum piperitum) is in the Kyoto cuisine was obvious with several shops profiling this spice in addition to restaurants and fast food outlets selling sansho dishes (pictures below).

See also my blog post celebrating my first harvest in Malvik: https://www.edimentals.com/blog/?p=34090

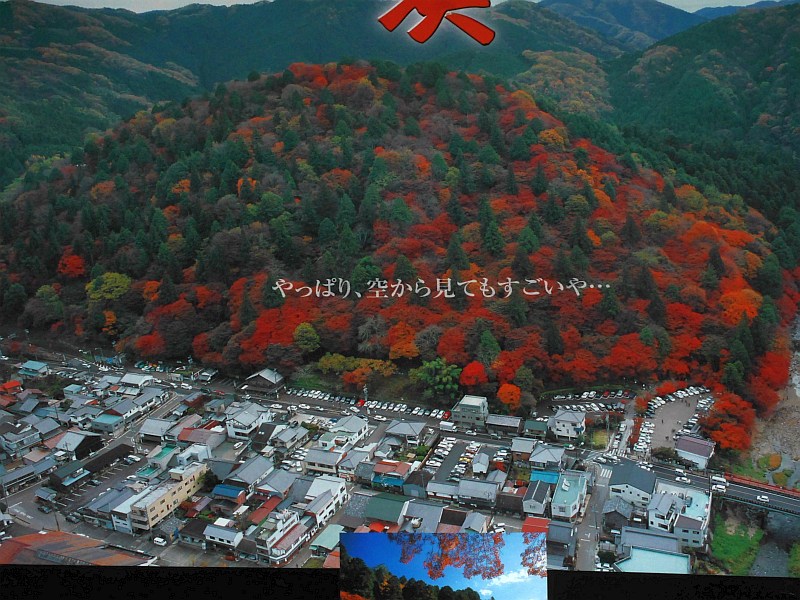

The genus Zanthoxylum includes some 250 species of deciduous and evergreen trees, shrubs and climbers in the citrus family, Rutaceae. Zanthoxylum piperitum is called sanshō (山椒) in Japan and chopi (초피) in Korea. I picked up a Japanese book “I want to know more about Kyoto Vegetables” by Koji Ueda which explains the superiority of the local sansho grown on Mt. Kurama about 15 km north of the city.

Translating from the book

“Some may question the inclusion of sansho berries among Kyoto vegetables, but for Kyoto residents, who strive for the softest vegetables, sansho berries are an essential Kyoto vegetable. Hatsuhashi and senmaizuke are ubiquitous souvenirs throughout Kyoto, but recently, chirimen sansho has become a staple, almost replacing senmaizuke. This is a tsukudani (simmered dish) of dried small sardines and sansho berries. Chirimen sansho’s success hinges on the tenderness of the sansho berries and their skin. In the past, it was a secret recipe passed down from mother to son from each family. When it comes to sansho berries with soft flesh and skin, the first thing that comes to mind is the sansho berries near Mount Kurama in Sakyo Ward, Kyoto City. The type of sansho is called Asakura sansho, and it’s grown in Tajima Province (Hyogo Prefecture).”

The city of Asakura is in Fukuoka Prefecture and here this special thornless variety of sansho originated. The book proceeds to explain that after choice of variety, the next most important thing is when the berries are harvested. If harvested too early they are soft, but break down when cooked in tsukudani. Harvested too late, the skin becomes hard and the berries turn black, turning the entire fruit into a hard, unappetising substance. When berries turn black greengrocers call it “the ohaguro has got in.” (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ohaguro). To ensure a good result, you need to use before “the ohaguro has got in”.

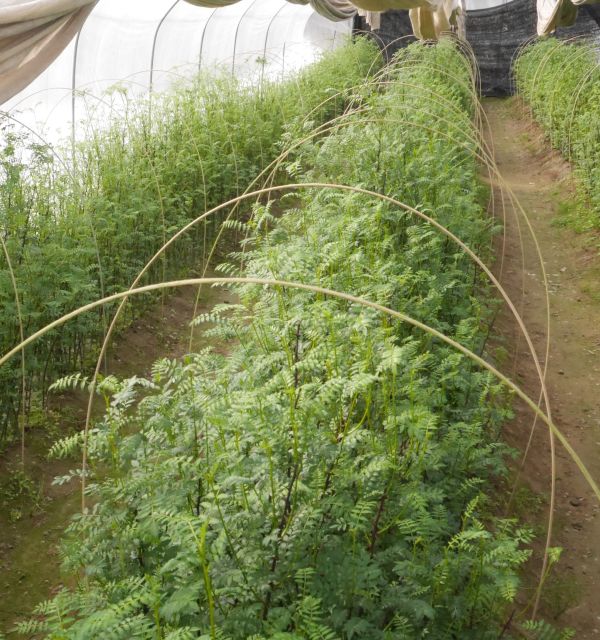

Other parts of this shrub are also used, including the young leaves, flower buds, flowers, bark and young fruits. One of the sansai farms we visited specialised on producing the leaves, used as a beautiful edimental garnish on various dishes. The leaves had to be “perfect” for use in this way. See the gallery of pictures below from the farm visit.

The female trees are grafted and prefer semi-shade. The male trees are also used, most commonly the green flowering buds or hana sansho, a seasonal product in spring (see https://tinyurl.com/bs29zdcs). It’s used as a garnish on various dishes, in tsukudani and other dishes.

The flowers are also used, typically sprinkled on soups and other dishes as a spicy garnish. Next available are the immature peppercorns known as Ao-sansho, literally green sansho and these are used in a similar way, in tsukudani, or mixed with dried small sardines to make chirimen-sansho.

There are even records of the inner bark being used in the past!

Zanthoxylum schinifolium is also found in the wild in Japan where it is known as inu-sansho or literally dog sansho, referring to the inferior taste of the berries.

5 forms of Zanthoxylum piperitum are named on the Japanese Wiki page:

Asakura forma inerme is a thornless cultivar that emerged as a result of a mutation in the 19th century or earlier. It is mainly grown by grafting female plants, as seedlings are sexually indeterminate (males don’t have berries) and can develop thorns. (I once saw this form in the Utrecht Botanical Garden with berries; pictures)

Yamaasakura forma brevispinosum is intermediate between the wild thorny species and Asakura with short spines, found wild in the mountains.

Ryujinzansho forma ovalifoliolatum has ovate leaflets and only 3-5 leaflets. They are considered edible, but not medicinal. Originates from the Ryujin region of Wakayama Prefecture

Grape sansho is believed to descend from the Asakura form and is suitable as it doesn’t grow very tall and produces large fruits, prolific like a bunch of grapes. It is cultivated by grafting female plants.

Takahara Sansho (Highland Pepper) is cultivated in the Takahara River basin in the Hida region, is smaller than Asakura sansho and is a fragrant variety.

The Zanthoxylum genus is also known as host of various species of swallowtail butterfly (Papilio sp.) both in North America and the Far East. In Southern Europe the migratory subspecies is known to feed on common rue / vinrute (Ruta sp.) and like Zanthoxylum in the Rutaceae! In 2024, caterpillars were found on a common rue plant being grown in the herb garden at the Ringve Botanical Garden in Trondheim! Perhaps it could turn up on cultivated Zanthoxylum species in Europe.