Monthly Archives: January 2017

New snow fjord views

Perennial kales in my loft room

Bullfinches in the garden

It’s back…and at 11:30 am, gone again!

Encounters with Angelica in Japan!

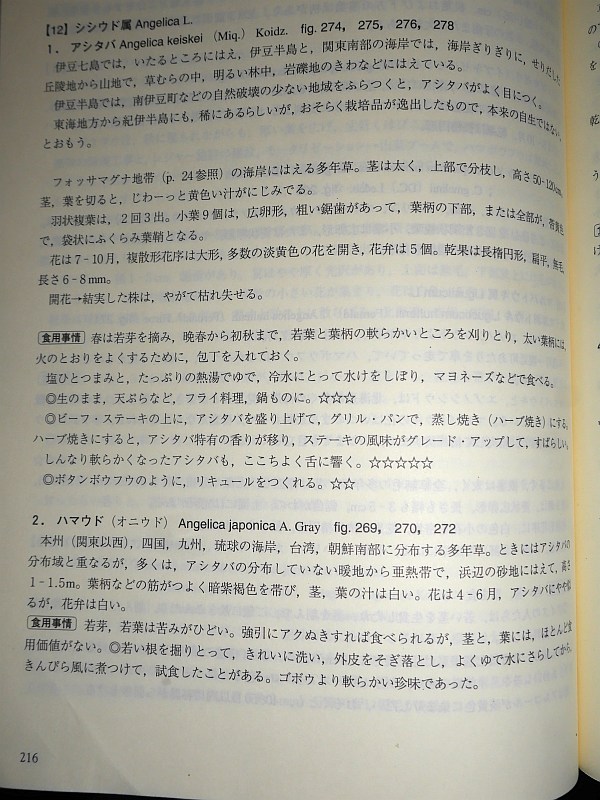

The genus Angelica has about 80 species distributed throughout the Northern hemisphere, of which around 25 are found in Japan. Around the world various Angelica species have been used traditionally for food and medicine, notably the Europe to Himalayas species Angelica archangelica, used since ancient times in various ways and the most well-known wild edible in Norway, where we have the domesticated form Vossakvann (see my book) with filled stems:

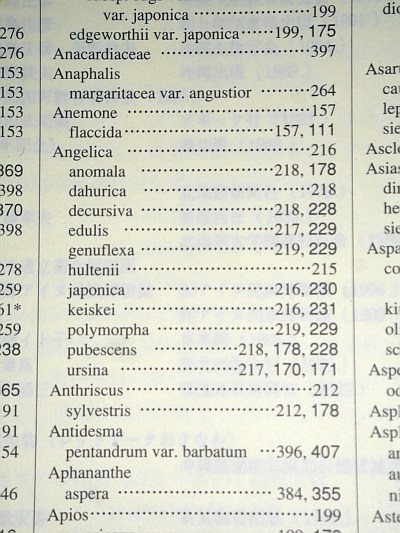

In Japan, no less than 11 species are covered in my most comprehensive Japanese foraging book, Ikozo Hashimoto’s Edible Wild Plants Encyclopedia (in Japanese). On my study trip to Japan in late March / early April 2016, we spent a few days on the scenic Izu Peninsula, a couple of hours from Tokyo. Here we found the best known Japanese species, Angelica keiskei (ashitaba) for sale in a supermarket (picture).

I wrote about my first encounter with this species here: http://www.edimentals.com/blog/?page_id=1385

(the Japanese name ashitaba means “tomorrow’s leaves”, referring to the plants very quick response to being damaged)

I wasn’t aware of it at the time, but ashitaba is endemic to the island Hachijō-jima (jima means island), one of a string of volcanic islands in the Pacific roughly 190 km south of Izu. Apart from Hachijō, ashitaba is cultivated on some of the other islands, including Izu Ōshima, Mikura-jima, Nii-jima and To-shima. It is also grown on the mainland (Honshū). Hachijo has a humid subtropical climate with very warm summers and mild winters, so it’s not surprising it didn’t overwinter in my garden and grew only slowly through the summer (more like winter in Hachijo!). It is an important plant for the local cuisine on the island where both the leaf and flower stalks, flower buds and roots are used in many types of dish from soba (buckwheat pasta), tempura, the alcoholic shōchū, as well as tea, cakes, konjac and even ice cream and is promoted for its health giving properties. In Izu oshima, it is fried in Camellia tea oil, an oil with a sweet, herbal aroma, cold-pressed from the seeds of Camellia oleifera. It is relatively strong tasting and is therefore mostly eaten in oily dishes like tempura or diluted for a milder taste. A nutrient analysis of ashitaba can be found here: http://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/gijyutu/gijyutu3/toushin/05031802/002/006.pdf

Interestingly, the variety grown on Mikura-jima is said to be the best as it is less bitter. This variety has “thick” stems, which calls to mind our own thick stemmed Vossakvann variety which is also milder tasting! Varieties on other islands are said to be distinct, having coloured stems.

The most common species we saw in southern Honshu was shiny leaved Angelica japonica (hamaudo, meaning Udo growing on the beach). Many consider it to be “poisonous” (which probably signifies that it is stronger tasting), but it certainly is used in similar ways to ashitaba and we even encountered a local foraging what was probably this species on Izu (see the film at http://www.edimentals.com/blog/?p=9672).

More information can be found in the captions below, which includes pictures of other Angelica species seen in botanical gardens in Kyoto and Tokyo and even ashitaba being grown as a house plant in the mountains near Nagano. My friend Andrew McMilllion in Southern Norway has discovered this wonderful plant and is growing it indoors (in flower as I write this in mid-January).

Thanks to Tei Kobayashi for showing me around on the visit to Nagano and Ken Minatoya-Yasuda for translating some of the text in my foraging book!

Seed sorting

I’m working on this year’s seed trade list and seed to be offered to Norwegian Seed Savers through our yearbook that will be published in February. I normally throw out seed that is more than 3 years old with a few exceptions, the collection year is marked on the packets. My seed are sorted into different categories and stored in my cold cellar in recycled milk carton boxes and similar for ease of finding:

My seed categories are:

- Seed for Norwegian Seed Savers (arranged alphabetically according to botanical name)

- Traditional vegetable seed – different boxes for Brassica, Root crops, Beans and peas and other veggies (includes e.g., chicories, annual onions, chili, quinoa, squash, tomato etc.) (arranged according to common names)

- Potatoes (seed potatoes stored in my cold cellar in recycled egg cartons)

- Seed of miscellaneous annual edibles

- Seed of perennials for trading (own saved seed, seed from trades that I had too much of), arranged alphabetically according to the botanical name

- Seed for stratifying (to be sown as soon as possible)

- Bulbils / topset onions for seed savers and trading kept individually in sour cream / yoghurt pots

- Diverse tubers (individually in sour cream / yoghurt pots)

- Seed / bulbils for sprouting indoors during the winter (for food)

Blomster på Matbordet i Nationen

Here is an article in Nationen, a Norwegian daily newspaper with a particular focus on agriculture, from my garden in 2011 by journalist Bente Haarstad. “Blomster på Matbordet” means literally “Flowers on the Edible Table”. It was written based on a garden visit on 11th August 2011 organised by the Trondheim Useful Plants Society (Trondheim sopp- og nyttevekstforening).

She also blogged about the visit here:

https://bentehaarstad.wordpress.com/2011/08/17/remember-to-eat-your-garden

..and here is an album of Bente’s pictures:

A journalist, Bjørg Hernes, from local newspaper Malvikbladet was also there and here is her article:

Finally, an album of pictures taken by my daughter, Hazel! The journalists are in these pictures as is the salad!

Wild edibles in SW England in late February

In late February last year I was in Cornwall for a short visit and had a head start on the year’s wild edible foraging with two less hardy species in particular that I’ve struggled to grow in the past….Alexanders (Smyrnium olusatrum), suspected to be one of the plants brought north by the Romans for food and common particularly on coastal areas in the UK, and Navelwort (Umbilicis rupestris), another plant at the north of its range in the UK. I was surprised to find Alexanders almost in flower, perfect for delicious stir-fried wild greens with Alexanders broccoli and navelwort greens served over soba (buckwheat pasta)!